After Closing the Laptop

After Closing the Laptop

A week before Chinese New Year, I was deep in high-intensity collaboration with AI. The workflow is hard to explain to people outside this field — I had five to ten Agents running simultaneously, each handling a different task. I was the dispatcher: breaking down requirements, distributing work, reviewing output. Code materialized in minutes. Documentation wrote itself. The iteration speed felt unreal.

It wasn't just "ten times more productive." It felt more like my intelligence had been parallelized — as if I suddenly had ten brains, each working on a different problem.

Two worlds, one person

Then I closed the laptop and went home for the holiday.

Small-Town Time

The drive from the high-speed rail station to my hometown takes forty minutes. Along the way, things looked different and the same — a few new chain stores with bright signs, but the hardware shop and barbershop next door hadn't changed in a decade. More delivery riders on e-bikes, but the traffic jams and honking rhythms were exactly as I remembered from school.

Back in town, relatives gathered, talking about the same things: whose kid got into which school, who built a new house, whose business had a rough year. Every person on the street was someone I knew, and the small talk hadn't evolved — "You're back! What are you doing out there?"

In their eyes, I'm "the one who does computer stuff." I'd spend thirty seconds explaining my job, they'd nod politely, and the conversation would move on. Nobody asked what "computer stuff" meant exactly. In the town's taxonomy, "does computer stuff" sat alongside "does trucking" and "does construction" — a label broad enough to need no further detail. Nobody needed to know I spent my days talking to AI and dispatching invisible digital workers.

I watched the older generation age a little more each year. I watched my child being passed around from relative to relative. Behind my laptop, I felt like I could do anything. Facing this, I couldn't do much at all.

The AI Red Envelope

On New Year's Eve, the TV played the Spring Festival Gala as always. This year, the show promoted Doubao — Bytedance's AI assistant. Relatives all downloaded it, but not to try AI. They wanted the red-envelope giveaway.

In my world, these large language models are productivity tools that might reshape entire industries. But in this living room, Doubao was just another red-envelope app, no different from Alipay's digital lucky-draw a few years back. AI-generated content was flooding their short-video feeds too, but to them it was just another form of entertainment.

Nobody was worried about AI replacing their job. Not because they'd assessed the risk and concluded it wouldn't — the question simply didn't exist in their frame of reference. The shop owners, truck drivers, farmers, small contractors — to them, AI was a new phone feature, roughly as notable as when mobile payments first appeared.

And they are the majority of this world.

My first instinct was to conclude that AI's disruption had been overhyped. But on reflection, that judgment felt premature.

The Shell and the Core

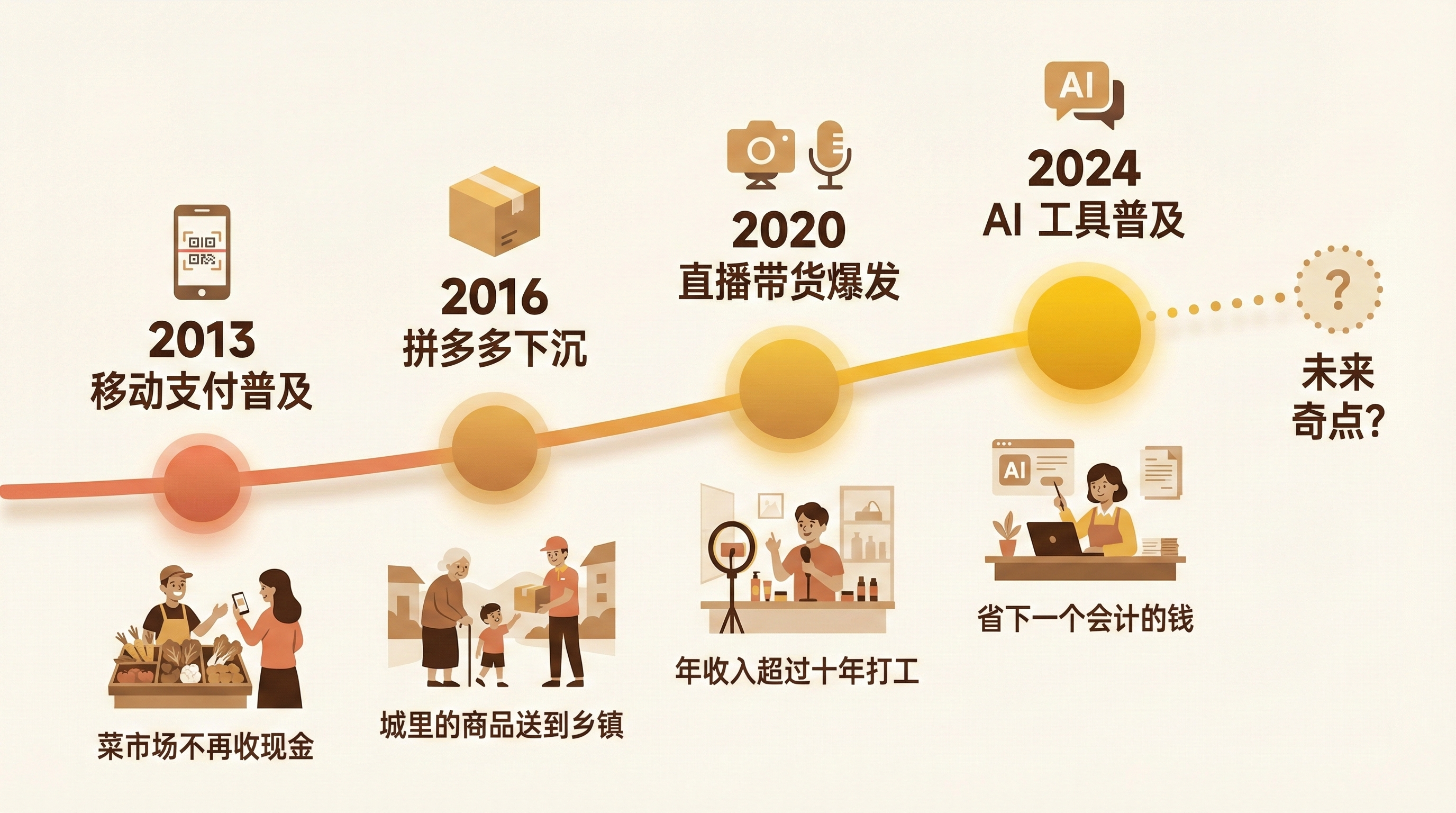

Think back. People in this town didn't think smartphones would change anything either. Around 2012, when the first wave switched to smartphones, the consensus was "it's a phone that plays videos." Nobody foresaw that cash would nearly vanish within a few years. Nobody foresaw that delivery platforms would bring chain brands to every small town. Nobody foresaw that livestream commerce would let some locals earn in one year what used to take ten.

Change doesn't arrive as a single morning when you wake up to a different world. It seeps in, layer by layer.

First, payment methods shifted — cash survived only for gift money at weddings and holidays, because those rituals demand the physical ceremony. Then consumption channels shifted — discount e-commerce gave small-town residents access to goods that once required a trip to the city. Then information channels shifted — short-video apps placed everyone in an information stream far beyond their locality.

But walking through town, it felt like nothing had changed. People still ate at the same noodle shop, still spent afternoons at the mahjong table, still followed the same holiday routines.

Here's what I'm getting at: the shell barely moved, but the core kept being replaced.

The shell and the core

The surface of a relationship-driven society — toasting elders, exchanging gift money, pulling strings — appeared untouched. But the underlying resource allocation had been quietly rewritten by efficiency, several times over. Whoever connected to new supply chains faster, whoever adopted new tools earlier, gained a new position within the same social network.

Last year, a Maybach showed up in town.

I don't know exactly what business the owner is in, but I'm nearly certain the wealth wasn't accumulated the traditional way. Maybe they caught an e-commerce window. Maybe they exploited an information gap. Maybe they used a new tool that made them an order of magnitude more efficient than their peers. The shell is the same — they still host dinners, raise toasts, hand out red envelopes, maintain the relationship network — but their core has already plugged into an entirely different efficiency system.

The history of human society, at bottom, is a history of efficiency. From agriculture to industry to the information age, each technological revolution didn't change human social nature — people will always need relationships, trust, and belonging. What changed was who could do more with less, and how that capability gap redrew the class lines.

Thirty Minutes

I only opened my laptop once during the entire holiday.

My father runs an agricultural supply business — fertilizers, pesticides, seeds. His method for tracking market prices hadn't changed in over a decade: every day, he'd scroll through WeChat groups and Moments, scanning what peers forwarded about pricing and industry news. The groups were noisy — useful information buried under ads and chatter. He'd sift through it himself, keep mental notes, make his own calls.

I watched him do this for a while. Then I opened my laptop and, in roughly thirty minutes, built him a tool — an automated scraper that pulls daily agricultural supply news and price movements, organizes them, and pushes a clean summary to him.

Thirty minutes. That's all it took me.

After a few days of using it, he told me he wanted to add a feature.

That caught me off guard. He didn't just say "this is nice" and move on. He had a new requirement. A man who'd been in the agricultural supply business for decades, after a few days with a tool his son made in half an hour, was already asking for more. He doesn't know what an Agent is. He doesn't know what a large language model is. But he knows this thing saves him half an hour of scrolling every day, and the information is more comprehensive than before.

He doesn't need to understand what AI is. He just needs to know that something made his business decisions a little faster and a little better-informed.

This is what efficiency permeation actually looks like. Not disruption. Not revolution. Not waking up one morning to a different world. It's a son who "does computer stuff" coming home for the holiday, spending thirty minutes on a small tool, and shifting his father's information flow from manually sifting WeChat groups to reading an auto-generated briefing. The shell didn't change — his father still visits peers, still relies on personal networks for sourcing, still closes deals over dinner — but the basis for his decisions has quietly become different.

Thirty minutes of transmission

The Silence of Quantitative Change

So back to AI.

When people in town treat Doubao as a red-envelope tool, that's not evidence that AI doesn't matter. It's the standard opening act of every wave of technological permeation. Smartphones were initially "phones that play videos." The internet was initially "a computer that lets you chat." People always interpret new tools through old frameworks first, cramming them into existing habits.

The real changes happen in the cracks nobody notices. A small business owner uses AI to organize invoices, saving the cost of a bookkeeper. A young content creator uses AI to batch-produce posts, doubling their following. A kid places in a competition thanks to AI tutoring. None of this makes the news.

The tool I built for my father is one of these cracks.

The silence of accumulation

Each accumulated efficiency gap is quantitative change. And when the quantitative change is enough, it reaches a tipping point. Just as mobile payment's gradual spread one day suddenly meant the wet market stopped accepting cash. Just as short video's gradual spread one day suddenly made young locals feel that livestreaming beat factory work. You never notice the exact day the tipping point arrives. You only look back one day and realize the world is already different.

Three Generations

Writing this, something occurred to me.

My child is still very young. But from day one, the way we made parenting decisions was already entirely different from the previous generation — we check feeding guidelines with AI, assess developmental milestones with AI, and when nothing works at 3 AM, the first instinct is to ask AI.

My father's information habits, built over decades, were partially replaced by something I made in thirty minutes. My child will never experience "replacement" at all — because AI was already there when they were born.

Three generations, three relationships with information. My father manually filters WeChat groups. I dispatch Agents. My child will probably think of AI the way we think of running water — something that was simply always there.

The sense of rupture I feel now — one world when the laptop is open, another when it's closed — is likely an experience unique to our generation. The previous generation doesn't have the "laptop open" world, so there's no rupture. The next generation won't remember the "laptop closed" world, so there's no rupture either.

Only us, caught exactly in between. One foot in an accelerating future, the other still sunk in an unhurried past.

Three generations, three relationships with information

Closing and Opening

So the dissonance that unsettled me may not be two worlds in opposition. It may be a permeation in progress, and I happened to cut a cross-section through it.

Behind the laptop, I live at the frontier of the efficiency revolution. I use the latest models, dispatch ten Agents at once, experiencing what it feels like when intelligence can be infinitely replicated.

Away from the laptop, I live in a world whose shell looks frozen in time. Relationships, small talk, toasts, gift money — everything follows a rhythm decades old.

But these two worlds aren't parallel. There's an invisible conduit between them, and efficiency seeps through it continuously, from one end to the other. The seepage is slow — so slow that people inside it can't feel it. But it never stops.

The gradient of efficiency permeation

I might be part of the conduit myself. A guy who "does computer stuff," home for the holiday, passing a small piece of efficiency through to the other side. My father caught it and asked for more. Maybe next year I'll build him something else. Maybe someone else from town, some other person who went out and "does something," is doing the same.

The Maybach owner has already passed through the conduit. Who passes through next, nobody knows. But when enough people do, the shell will no longer hold, and life in town will eventually become something else.

Only when that day comes, the people living through it probably still won't feel anything dramatic happened. They'll just think: this New Year felt a little different from last year.

And my child might one day ask me: Dad, what was it like before AI?

I'll probably say: Your grandfather used to scroll through WeChat groups every day to check prices. Did that for over a decade. Then one New Year, I spent thirty minutes building him a little tool.

They might ask: Why didn't you do it sooner?

I won't know how to answer that.